This post was co-written with Katia Hildebrandt and also appears on her blog.

This week (June 5-11) we’ll be hosting a couple of events and activities related to digital citizenship as part of a series of DigCiz conversations. Specifically, we’d like to deepen the discussion around digital citizenship by asking how we might move from a model of personal responsibility (staying safe online) to one that takes up issues of equity, justice, and other uncomfortable concepts. That is, we want to think about what it might look like to think about digital citizenship in a way that more closely resembles the way we often think about citizenship in face-to-face contexts, where the idea of being a citizen extends beyond our rights and also includes our responsibility to be active and contributing members of our communities. Of course, that’s not to say that face-to-face citizenship is by default more active, but we would argue that we tend to place more emphasis on active citizenship in those settings than we do when we discuss it in its digital iteration.

So…in order to kick things off this week, we wrote this short post to provide a bit more background on the area we’ll be tackling.

Digital Citizenship 1.0: Cybersafety

The idea of digital citizenship is clearly influenced by the idea of “Cybersafety,†which was the predominant framework for thinking about online behaviours and interactions for many years (and still is in many places). This model is focused heavily on what not to do, and it relies on scare-tactics that are designed to instill a fear of online dangers in young people. This video, titled “Everyone knows Sarah,†is a good example of a cybersafety approach to online interactions:

The cybersafety approach is problematic for a number of reasons. We won’t go into them in depth here, but they basically boil down to the fact that students aren’t likely to see PSAs like this one and then decide to go off the grid; the digital world is inseparable from face-to-face contexts, especially for today’s young people who were born into this hyper-connected era. So this is where digital citizenship comes in: instead of scaring kids offline or telling them what not to do, we should support them in doing good, productive, and meaningful things online.

From Cybersafety to Digital Citizenship

Luckily, in many spheres, we have seen a shift away from cybersafety (and towards digital citizenship) in the last several years, and this shift has slowly found its way into education. In 2015, we were hired by our province’s Ministry of Education to create a planning document to help schools and districts with the integration of the digital citizenship curriculum. The resulting guide, Digital Citizenship Education in Saskatchewan Schools, can be found here. In the guide, we noted:

“Digital citizenship asks us to consider how we act as members of a network of people that includes both our next-door neighbours and individuals on the other side of the planet and requires an awareness of the ways in which technology mediates our participation in this network. It may be defined as ‘the norms of appropriate and responsible online behaviour’ or as ‘the quality of habits, actions, and consumption patterns that impact the ecology of digital content and communities.’â€

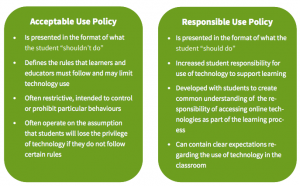

In the Digital Citizenship Guide, we also underlined the importance of moving from a fear- and avoidance-based model to one that emphasizes the actions that a responsible digital citizen should take. For instance, we suggested that schools move away from “acceptable use†policies (which take up the cybersafety model) and work to adopt “responsible use†policies:

Moving Beyond Personal Responsibility

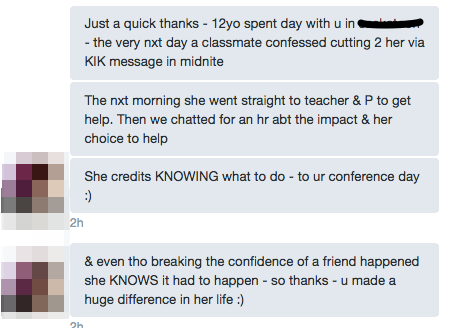

While the move from cybersafety to digital citizenship has helped us to shift the focus away from what not to do online, there is still a tendency to focus digital citizenship instruction on individual habits and behaviours. Students are taught to use secure passwords, to find a healthy balance between screen time and offline time, to safeguard their digital identity. And while all of these skills are important pieces of being a good digital citizen, they revolve around protecting oneself, not helping others or contributing to the wider community.

So we’d like to offer a different model for approaching the idea of citizenship, one that moves beyond the individual. To do this, we have found it helpful to think about citizenship using Joel Westheimer’s framework. Westheimer distinguishes between three kinds of citizens: the personally responsible citizen, the participatory citizen, and the justice oriented citizen. The table below helps to define each type.

Using this model, we would argue that much of the existing dialogue around digital citizenship is still heavily focused on the personally responsibility model. Again, this is an important facet of citizenship – we need to be personally responsible citizens as a basis for the other types. But this model does not go far enough. Just as we would argue that we need participatory and justice-oriented citizens in face-to-face contexts, we need these citizens in online spaces as well.

So here’s our challenge this week: Is there a need to move beyond personal responsibility models of digital citizenship? And if so, how can we reframe the conversation around digital citizenship to aim towards the latter two kinds of citizen? How might we rethink digital citizenship in order to encourage more active (digital) citizenship and to begin deconstructing the justice and equity issues that continue to negatively affect those in online spaces, particularly those who are already marginalized in face-to-face contexts? And what are the implications of undertaking this shift when it comes to our individual personal and professional contexts, especially when it comes to modelling online behaviours and building (digital) identities/communities with our students?

These are big questions, and we certainly don’t have the answers yet – so we’d love to hear from you! Please consider commenting/responding in your own post, or come join us as we unpack these complex topics during the events listed below.

This week’s events:

- On Tuesday, June 6 at 3 pm EDT, we will be hosting a webinar to discuss this week’s topic. If you are interested in being a panelist, please email us at alecandkatia@gmail.com – we’d love to have you join us! The Webinar will take place via Zoom.Us – to join as an attendee, just click this link.

- On Wednesday, June 7 at 8 pm EDT, we will be moderating a Twitter chat with a number of questions related to this week’s topic. To join, please connect with us on Twitter (@courosa and @kbhildebrandt) and follow the #DigCiz hashtag.