This post was written jointly with Katia Hildebrandt and also appears on her blog.

Recently, we presented at OER15 in Cardiff, Wales, on the topic of developing a framework for open courses. In our session, we considered our experiences in facilitating MOOC type courses in order to think through and address the challenges that these types of courses present.

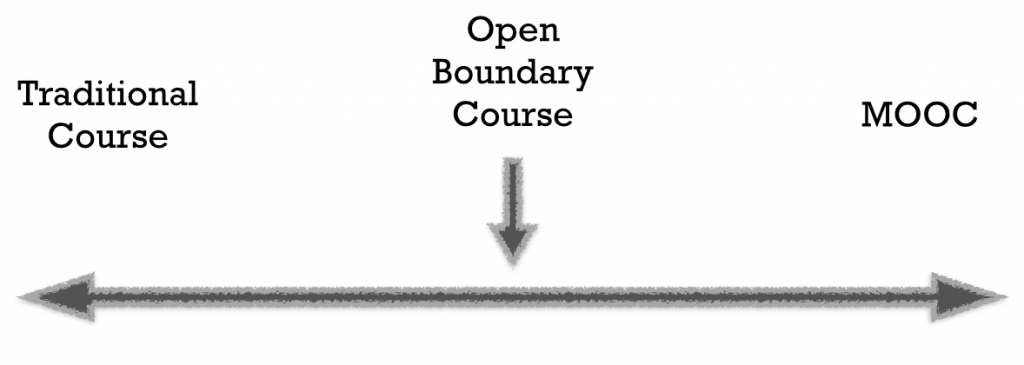

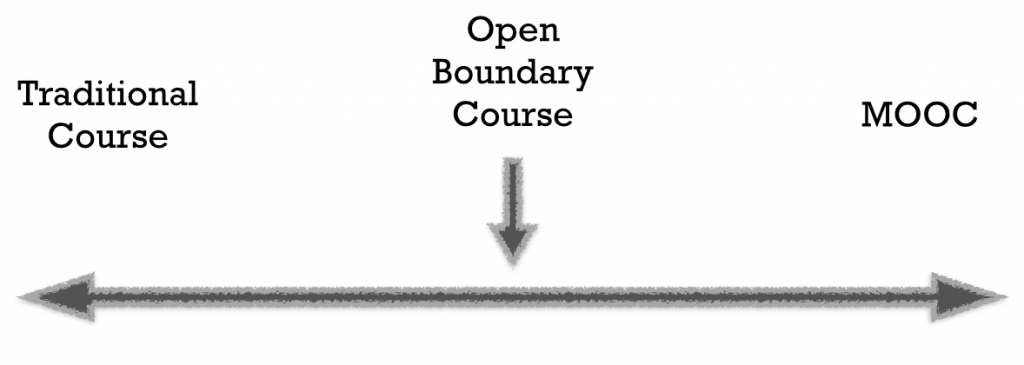

So first, a little background: It has been stated that there are two general categories of MOOCs: xMOOCs and cMOOCs. xMOOCs are large-scale MOOCs that often consist of video-delivered content and automated assessments. These MOOCs are often offered by institutions or by large-scale MOOC providers like edX and Coursera. cMOOCs, or Connectivist MOOCs, are network-based: they operate through a distributed pedagogy model, where the connections become as important as the content, knowledge is socially constructed by the group, and participants learn from each other. In many ways, these courses can be similar to learning on the open web: there is minimal guidance in terms of what is learned and when, and participants are instead free to engage with the course in whatever way they choose. Open boundary courses, meanwhile, are for-credit courses (such as those offered by a post-secondary institution) that are opened to the public on a non-credit basis. For instance, the ds106 Digital Storytelling course, originally based out of the University of Mary Washington, is also offered as an open boundary course. If you were to imagine the spectrum of openness in courses, it might look something like this:

For the purposes of this post, we take the term “open course†to include both open boundary courses and MOOCs (particularly cMOOCs).

Much of our insight into open courses comes from our work with three large, open courses: EC&I 831 (Social Media and Open Education), #ETMOOC, and #DCMOOC. The latter two courses were both cMOOCs; #ETMOOC (a MOOC about educational technology) ran in the winter of 2013, and #DCMOOC (a MOOC about digital citizenship sponsored by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Education) ran in the spring of 2014. EC&I 831, meanwhile, is a graduate level class at the University of Regina that was developed and then taught for the first time in 2007 and has run every year since. While the course has a core group of for-credit graduate students, it is also open to anyone – classes are held online and the link to the web-conferencing platform is tweeted out each week, so that anyone is free to join any given session. EC&I 831 is not a MOOC; instead, it is considered an open-boundary course, and it’s generally seen as one of the forerunners for the MOOC movement.

One of the common features of MOOCs is the high drop-out rate, which occurs for a variety of reasons. The drop-out rate is not in itself necessarily a negative: it may mean that students have the freedom to try out different courses (or other educational experiences) until they find one that fits their needs, or it may mean that students are choosing to audit only particular portions of courses rather than completing them in their entirety. However, some students drop out or engage very minimally with open courses not due to lack of interest or fit with their own needs but because the format and ethos of cMOOCs can be difficult to navigate for those who have not spent much time learning on the open web. However, with EC&I831, #ETMOOC, and #DCMOOC, we have seen a significant level of engagement, persistence, and follow-through with the courses. Perhaps more importantly, many of the participants have stayed engaged with the course community and gone on to become leaders in their own networks; for instance, former participants in #ETMOOC organized their own 2nd year anniversary chat. So the question is, how do we take the strategies that led to positive and lasting outcomes in these courses and apply them to other large, open courses in order to help make participants’ experiences more positive, relevant, and beneficial in the long term?

Below, we identify seven elements of course design that we have used in our own open courses. Then, we suggest possible strategies for building a framework for open courses that might lead to more positive student involvement, in the hopes that these favourable experiences will lead students to continue learning and connecting in open, networked spaces.

- Semi-structured course environment

The challenge: The incredible choice of online spaces and tools can be overwhelming to those just starting to learn on the open web.

The strategy: In the open courses that we have facilitated, we help students to gradually ease into the greater digital world through the creation of a variety of interconnected course environments with varying levels of privacy. This can help to gradually “thin the walls†of the more traditional closed classroom environment:

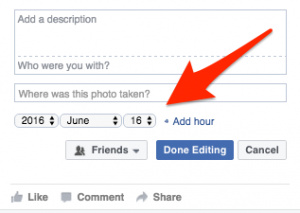

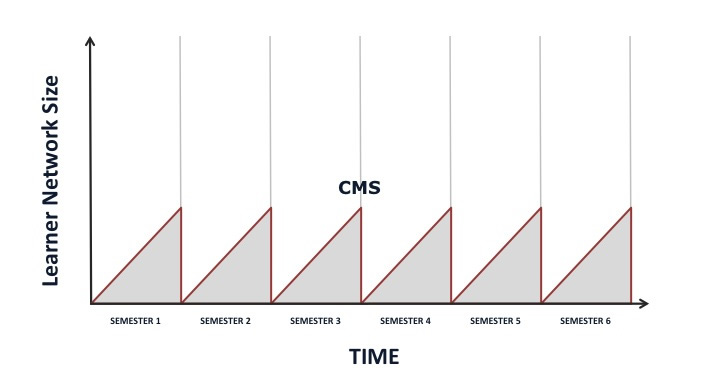

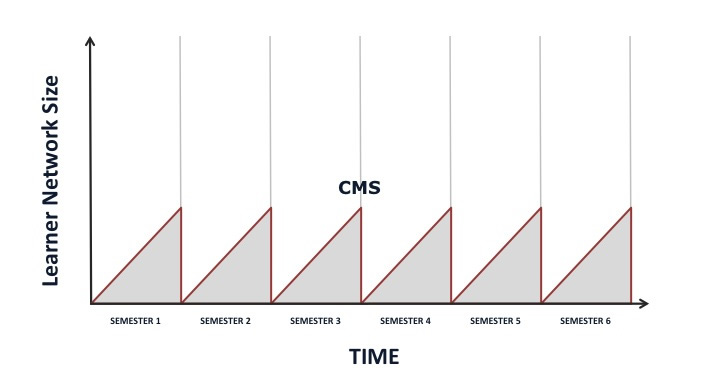

Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown write: “The new culture of learning actually comprises two elements. The first is a massive information network that provides almost unlimited and resources to learn about anything. The second is a bounded and structured environment that allows unlimited agency to build and experiment with things within those boundaries.†Keeping this in mind, we design the course environment as a bounded space for learning how to learn that exists within the larger space of the open web; we do this through a combination of different tools (small tools, loosely joined). While our use of specific tools has evolved and changed over time, what is important is the way in which the chosen tools work together in combination to ensure a particular set of affordances. In the current iteration, for instance, we allow for private interactions in a “safe†space by creating a Google Plus community for each of our courses, where students can pose questions, engage in discussion, and share resources. As well, we encourage students to develop their own spaces on the web, but we also employ mechanisms to keep these spaces interconnected in order to create a structure of support. For instance, students create their own personal blogs or ePortfolios, but these sites are aggregated using the FeedWordPress plugin so that posts also appear on a central course hub. Additionally, students develop individual Twitter accounts but remain connected through the creation of a Twitter list and the use of a course hashtag (for instance, #eci831). In this way, students are eased into the open web, but at the end of the course they are left with their own individually controlled spaces, which they can continue to use and expand or, alternatively, choose to delete entirely. The ability for students to continue to grow the networks that they have begun to build in class is markedly different from what happens with a traditional Learning/Content Management System (LMS/CMS), where the course is archived at the end of the semester and students start back at zero.

- Interest-based curriculum

The challenge: The overwhelming array of information available online can make it difficult to find a place to begin or a path to take.

The strategy: Martin Weller describes the wealth of knowledge online as a potential “pedagogy of abundance.†For learners who are more used to a structured curriculum, this can make getting started a challenge. However, learning is most meaningful when it is interest-based. So, in our courses, we want to avoid setting a strict scope and sequence type curriculum; instead, we encourage students to let their interests become the catalyst for learning. One particularly successful strategy has been the inclusion of student learning projects in our courses, where students are expected to learn a skill of their choice using online resources and then document the learning process. This allows students to choose a high interest topic, but it also ensures that all students are documenting their learning in a similar manner, which can provide a social glue as students discuss the methods and tools use for documentation (which is a digital literacy skill in itself). As well, weekly synchronous video conferencing sessions and weekly Twitter chats can keep students from feeling lost or disconnected.

- Assessment as learning/connection

The challenge: A lack of check-ins/endpoints in online learning can make the learning process seem nebulous.

The strategy: Traditional for-credit courses include assignments that allow students to demonstrate their learning; for instance, in EC&I 831, students create summaries of learning that let them to express their learning using the tools of the open web. These summaries also allow students to practice designing and sharing media in the collapsed context of our networked world, often leading to serendipitous feedback from others outside of the course. Although MOOC-type open courses do not have the same sort of endpoint (as the hope is that learning will continue beyond the course), implementing a similar type of checkpoint – a summary-type assessment that allows students to put tools and theory into practice – can be helpful to allow students to consolidate their learning as well as to connect further through sharing and participating in their newly build networks.

- Instructor support

The challenge: The large student-instructor ratio in large open courses can lead to students feeling lost and unsupported as they explore new forms of media.

The strategy: We’ve found that in large courses, it is helpful to have a variety of orientation sessions (for instance, a session on blogging or on using Twitter) in order to help students gain a level of comfort with course tools. This is especially important because students come to courses with an increasingly wide range of digital literacies and technological competencies; while students will work towards attaining a level of digital fluency throughout the course, these introductory sessions give students the basic skills they need in order to access the learning experience of the course.

As well, although we design courses to encourage a high level of peer feedback (or even feedback from others not officially participating in the course), it is important to ensure that all students are getting regular feedback and suggestions for improvement so that they are able to continue to grow; thus, it is helpful to ensure that the facilitation team include members who act as “community developers,†individuals who can comment on student blogs, interact with participants on Twitter and Google Plus, and address any questions that arise; in #ETMOOC, for instance, having a group of co-conspirators meant that the work of community development and course leadership did not fall on a single individual.

- Student community

The challenge: Newcomers to online networks can often feel isolated and alone.

The strategy: In a graduate course like EC&I 831, there is a core group of for-credit students with similar aims, and this creates an immediate, built-in Personal Learning Network (PLN). But in larger MOOCs, this core group doesn’t exist, and so facilitators need to work to build a student community through group-building activities. For instance, in #ETMOOC, facilitators organized and created a lipdub video in which course participants could take part. In another recent course, students started a Fitbit group, which allowed course participants to bond over a shared activity. Activities that help to create a sense of presence in the course (such as asking participants to write an introductory blog post or having students create short videos of themselves using a tool like Flipgrid) can help to build a sense of community. Importantly, such community-building activities also help students to build their own PLNs while adding an increased level of personal accountability that can encourage participants to continue with the course.

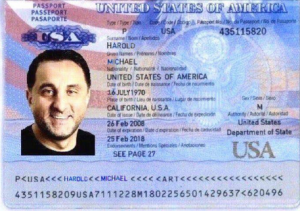

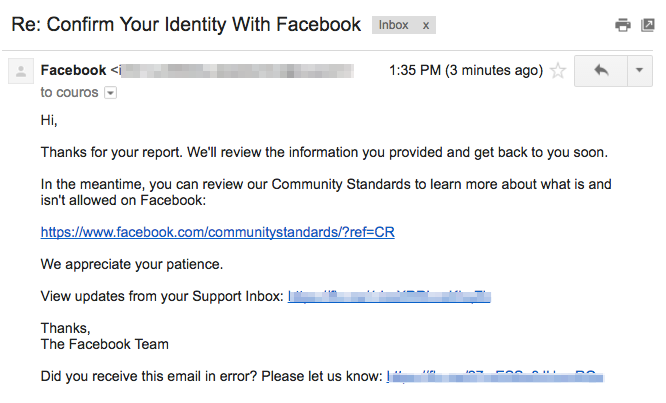

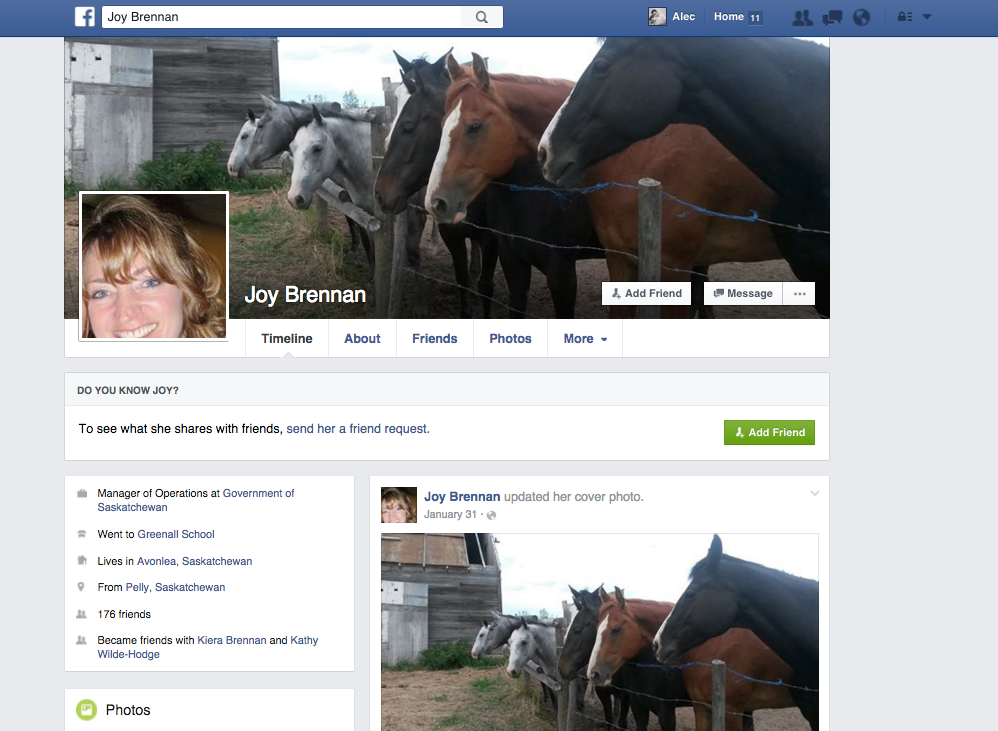

- Digital identity creation

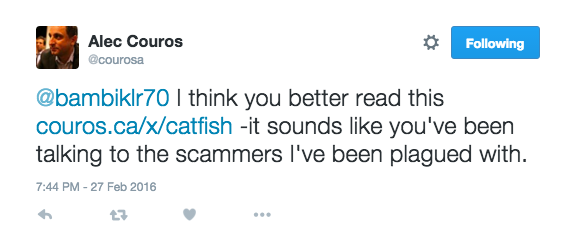

The challenge: Missteps and mistakes can be amplified in digital spaces, where footprints are permanent and easily searchable.

The strategy: In a world where online reputation is becoming increasingly important, it is critical that we take control of our digital presence so that others don’t do so for us. As well, in order to participate more fully in MOOCs in particular and in a PLN in general, it’s important to declare oneself; what we get from our networks depends largely upon what we contribute to them, and it’s difficult to contribute without a digital presence. That might mean creating a blog, developing a Twitter presence, or engaging on other social networking sites. Supporting the development of students’ digital identities as part of open courses will not only help them to network as part of the course, but it will also serve them well in the long term.

- Democratizing the web

The challenge: Those new to digital spaces can be hesitant to voice their beliefs publicly due to the nature of digital artefacts, which can easily be shared, remixed, and taken out of context.

The strategy: As digital citizens, we have a responsibility to keep the web democratic and allow for equitable expression, but it can be difficult for non-dominant views to be voiced online due to fear of criticism or other negative repercussions. However, silence can often be taken as complicity, so we need to support students in open courses as they delve into potentially controversial topics, by fostering a community in which students feel more confident expressing viewpoints with the support of a group, and by using our own digital identities to model what it looks like to speak out for social justice issues online.

Although the nature of MOOCs and open courses can present difficulties for those who are new to learning on the open web, these strategies can help to give participants a foothold in the online world, which can, in turn, increase their chances for a meaningful experience that paves the way for a lifetime of learning.